The ability to target malignant cells without damage to surrounding healthy ones has been a long-sought goal in cancer drug development. Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) have been investigated as one such solution aimed at delivering more targeted therapies. ADCs — an approach first envisioned by Paul Ehrlich in the early 20th century — combine the targeting function of antibodies with a cytotoxic payload. First generation ADCs, developed in the early 2000s, mostly did not live up to expectations due to lack of efficacy or excessive toxicity. ADCs are complex drugs whose success can be affected by many factors, including the selectivity of the targeting antibody, the stability of the ADC construct, and the efficiency of the cytotoxic payload in killing targeted cells while producing limited off-target side effects.

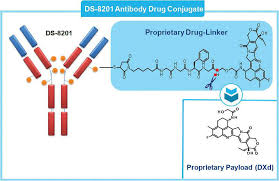

However, the field of ADC development is now generating new excitement, partly driven by the success of a breast cancer treatment, DS-8201, developed by Daiichi Sankyo and recently partnered with AstraZeneca in a deal worth up to $6.9 billion.

DS-8201 carries eight toxin payloads to cancer cells, double that of previous ADCs. In pivotal clinical trials, it has doubled the survival time for advanced breast cancer patients to 20 months, from an average of 10 months for chemotherapy, and patients experience less nausea and hair loss. AstraZeneca plans to file for FDA approval of DS-8201 in September for the treatment of HER-2 positive metastatic breast cancer previously treated with Kadcyla (ado-trastuzumab emtansine), and to begin testing the ADC in first-line treatment of the disease within the next two years.

DS-8201 carries eight toxin payloads to cancer cells, double that of previous ADCs. In pivotal clinical trials, it has doubled the survival time for advanced breast cancer patients to 20 months, from an average of 10 months for chemotherapy, and patients experience less nausea and hair loss. AstraZeneca plans to file for FDA approval of DS-8201 in September for the treatment of HER-2 positive metastatic breast cancer previously treated with Kadcyla (ado-trastuzumab emtansine), and to begin testing the ADC in first-line treatment of the disease within the next two years.

Experts estimate that DS-8201 could potentially triple the number of patients who receive targeted treatment for breast cancer. Drugs like Herceptin only target cancers expressing high levels of HER2, while breast cancer patients with lower levels rely on hormone therapy or chemotherapy. DS-8201 has the potential to treat patients with both high and low HER2 levels, thus offering a possible replacement for both Herceptin and chemotherapy in the treatment of breast cancers.

Today over 50 companies are developing ADC drug candidates for cancer, often in combination with checkpoint inhibitors.

In June, Roche received an early approval for its ADC, Polivy (polatuzumab vedotin), for the treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) that has either relapsed or become resistant to previous therapies. Polivy targets the CD79b receptor on B cells, and releases its toxic payload when the antibody binds to the B cell. In a Phase 2 clinical trial, Roche paired Polivy with Rituxan and an older chemotherapeutic drug, bendamustine. The combination regimen produced a complete response in 16 of 40 treated patients, versus 7 of 40 for a control group receiving Rituxan and bendamustine alone. Roche is now testing the Polivy/Rituxan/chemotherapy combination in previously untreated DLBCL patients. The combination is likely to compete with or serve as a first treatment before moving to CAR-T therapies, which have been approved for the same patient population. The Polivy combination offers a significant advantage over CAR-T, as it can be given to patients with aggressive cancer right away, while CAR-T treatments require weeks of processing time.

In June, Roche received an early approval for its ADC, Polivy (polatuzumab vedotin), for the treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) that has either relapsed or become resistant to previous therapies. Polivy targets the CD79b receptor on B cells, and releases its toxic payload when the antibody binds to the B cell. In a Phase 2 clinical trial, Roche paired Polivy with Rituxan and an older chemotherapeutic drug, bendamustine. The combination regimen produced a complete response in 16 of 40 treated patients, versus 7 of 40 for a control group receiving Rituxan and bendamustine alone. Roche is now testing the Polivy/Rituxan/chemotherapy combination in previously untreated DLBCL patients. The combination is likely to compete with or serve as a first treatment before moving to CAR-T therapies, which have been approved for the same patient population. The Polivy combination offers a significant advantage over CAR-T, as it can be given to patients with aggressive cancer right away, while CAR-T treatments require weeks of processing time.

Astellas/Seattle Genetics also plans to file for approval of an ADC by year-end 2019. Their drug candidate, enfortumab vedotin, targets nectin-4, a protein found on multiple cancers. In a Phase 2 trial in patients with advanced urothelial cancer, the ADC produced a 44% overall response rate, with 12% of patients experiencing a complete response. Median survival increased by 7.6 months over standard of care, and the ADC worked across all patient groups including those that did not respond to checkpoint inhibitors, those with liver metastases, and those who had received three or more prior treatments. The standard treatment for urothelial cancers is a toxic, cumbersome chemotherapeutic regimen, and half of treated patients relapse within two years. Some then receive a checkpoint inhibitor, which only works in 20% of those patients.

However, not all recent ADCs have been as successful. ImmunoGen’s anti-folate receptor alpha ADC, mirvetuximab soravtansine, failed to meet its primary endpoint of overall survival in a Phase 3 monotherapy trial in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer, although the ADC successfully shrunk tumors and showed fewer adverse events compared to chemotherapy. Moreover, AbbVie’s ADC Depatux-M (depatuxizumab mafodotin), which targets a mutated form of the epidermal growth factor receptor, failed to show a survival benefit in a Phase 3 trial in patients with glioblastoma, one of the most difficult cancers to treat.